Joseph Campbell is known in large part for the dizzying scope of his knowledge. He spent his life immersed in the study of myths across cultures, across geographical areas, across time periods, in multiple ancient and modern languages and produced a body of scholarship unrivaled in its breadth. However, the notable aspect of Campbell’s work is not so much its exhaustive scope, but its synthesis of common themes, archetypes, fundamental questions and aspects of the human condition that seem to transverse all humanity. The scope of his study bears witness to what is shared among us and to that which the psychologist, Carl Jung, would say resides in the collective unconscious. Due to this broad study Campbell is able to speak to both these impressive elements of sameness as well as to the treasures unique to particular locations, people, and times.

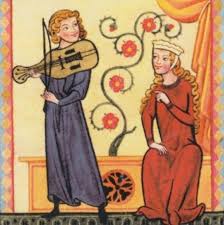

So, what does this have to do with love? When asked where to begin a conversation about love in Western culture, Campbell usually points to the troubadours of 12th century Provence. In Germany, as the troubadour culture began to spread around Europe, they became known as the Minnesingers, the singers of love. The arrival of the troubadours marks the first time that love entered the world as a person-to-person relationship, the way we most commonly think of it now. Prior to this birth and blossoming in the 12th century, love was experienced as either “eros” or “agape.” Both eros and agape are impersonal ways of loving. Eros is made manifest in sexual desire, as Campbell says, “a zeal of the organs for each other.” Agape is love thy neighbor as thyself, spiritual love. It is compassion, the opening of the heart, but it is not individuated. So here in the 12th century enters Amor! The troubadours recognized Amor as the highest spiritual experience, an experience that awakens from the meeting of the eyes. Campbell goes on to suggest that this transformation of love, toward a personal and individual experience becomes essentially THE defining aspect of the West. The courage to love became the courage to affirm a personal spiritual experience.

Campbell illuminates the idea that in affirming one’s own personal experience there was an outlet to defy tradition. To give validity to the individuals’ experience of what humanity is, what life is, what values are, directly bucked the oppressive heavy-handed medieval church and gave rise to this new power. Campbell delights in the synchronicity of AMOR being ROMA spelled backwards, as Rome (Roma in Italian) was (and is) the seat of the Papacy, the heart of the corrupt medieval church.

In traditional cultures, marriage itself was a family arrangement and still is in many parts of the world. These were the kind of marriages that were sanctified by the medieval church – purely political and social in nature. To go against this tradition was not only heresy but according to the church a kind of spiritual adultery, and the stakes were high – namely eternal damnation. These church sanctified marriages were opposite to the spiritual union named by the troubadours that begins with the meeting of the eyes, and this movement validating individual choice in the face of great danger is the underpinning of Campbell’s well-known dictum, “follow your bliss.”

Campbell uses the story of Tristan and Isolde to illustrate the danger and pain of this new kind of love. Toward the end of the story Isolde’s nurse realizes that Tristan and Isolde have both drunk a love potion meant for Isolde and King Mark (whom Isolde is meant to marry, but has never met). The nurse goes to Tristan and says, “You have drunk your death.” Tristan, deeply in love with Isolde, responds by saying, “If by my death you mean this agony of love, that is my life. If by my death you mean the punishment we are to suffer if discovered, I accept that. And if by my death you mean eternal punishment in the fires of hell, I accept that too.” The significance of this statement, Campbell explains, is that Tristan is saying that his love is bigger even than death and pain, than anything. It is an affirmation of the pain of life. And that in following your bliss, choosing a career path, etc., decisions should be made with that same sense, that no one can frighten you off from this path, no matter what happens it is the validation of life.

In this way, love, the way the troubadours understood it in the 12th century, can never be a sin no matter what the church (outer authority) says, love is the meaning of life and its highest point. Tristan and Isolde, William Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Dante’s meeting with Francesca and Paolo in hell: the point of all of these pioneers in love is that they decide to be the author and means of their own self-fulfillment, their own self-realization, and that realization is that what you love is your noblest work, and that wisdom comes from individual experience and not from dogma, politics, or society. For Campbell, the best part of the Western tradition has included a recognition of and respect for the individual as a living entity, and this recognition stems first from the way the troubadours imagined a new way to love.

So what were the rules of courtly love? First, to achieve the love of the woman, expressed in whatever form she chose, there was one essential requirement, and that was that one must have a gentle heart, a heart capable of love (not simply of lust). Campbell defines this quality as a heart capable of compassion. Compassion means suffering with. “Passion” is suffering and “com-” is with. The idea was to discover whether or not a man would suffer for love. In many ways the idea of this “test” remains in our modern day love-culture. If a woman was considered too ruthless, for example asking her lover to risk death she was called “sauvage” or “savage.” Furthermore, a woman who gave her love without testing enough was also called “savage.” Again, we see these boundaries placed on the behavior of women in the modern day as well. It’s important to note however that the troubadours were not aiming for carnal intercourse or to dissolve marriages, rather as Campbell writes, “they celebrated life directly in the experience of love as a refining, sublimating force, opening the heart to the sad bittersweet melody of being through love, one’s own anguish and one’s own joy.” The idea was to “sublimate life into a spiritual plane of experiences.” What the troubadours ultimately discovered was individual experience and individual commitment to experience.

The Grail legends fit into this schema in very beautiful ways as well. Campbell reveals that in the Grail legends, The Grail becomes that which is attained and realized by people who have lived their own lives. “The Grail becomes symbolic of an authentic life that is lived in terms of its own volition, in terms of its own impulse system, that carries itself between the pairs of opposites of good and evil, light and dark.” The impulses of nature are what give authenticity to life, not the rules coming from an authority. In this sense, what happened in the 12th century was one of the most important mutations of human feeling and spiritual consciousness to occur in the West, that a new way of experiencing love came into expression, a way of experiencing love that was in opposition to ecclesiastical despotism over the heart. “Love was a divine visitation.”

Lastly, the link between love and pain weaves its way through this understanding as well. The German theologian, Meister Eckhart said, “Love knows no pain,” and strangely this is also what Tristan meant when he said, “I’m willing to accept the pains of hell for my love.” There is nothing above it. This, however, does not preclude suffering. Campbell says, “The pain of love is not the other kind of pain, it is the pain of life. Where your pain is, there is your life… Love itself is the pain of being truly alive.” To me this means that the search for what you love authentically is endlessly worth whatever suffering occurs along the way, for that is your life’s work, to commit to love and to your own individual experience of where you discover it and where it discovers you.

* Joseph Campbell writes beautifully about Love in many of books; for this post I primarily used his chapter “Tales of Love and Marriage” in The Power of Myth, and “The Mythology of Love” in Myths to Live By.